Amazon Profiler and AWS CodeGuru Profiler — CI/CD

Table of contents

In this article I will go into details of the CI/CD pipelines my team implemented while at Amazon. Read my previous article for “The CI/CD Flywheel” to understand how each of the pipeline segments we will explore maps to the software release lifecycle.

Important notice

Amazon is a huge company, with hundreds of engineering teams.

The examples showcased below are based on my own experience. However, you should keep in mind that each team, organisation, department, could follow different practices, sometimes in significant ways.

Anything described in this article should not be extrapolated to be how the whole company worked. As you will see, even within my teams, we had different processes for several things.

You can find a more generic description of Amazon/AWS deployment pipelines in these amazing articles in the Amazon Builders’ Library, both written by Clare Liguori:

Amazon Profiler

I was in the Amazon Profiler team for about three years before leaving Amazon in 2020. Our product was continuous CPU profiling [1] [2] for the internal backend services, mostly targeting JVM services.

In this team we were doing trunk-based development for all our services, and all Pull Requests were merged into a single mainline branch.

Let’s explore the CI/CD setup for one of our backend services, and our website.

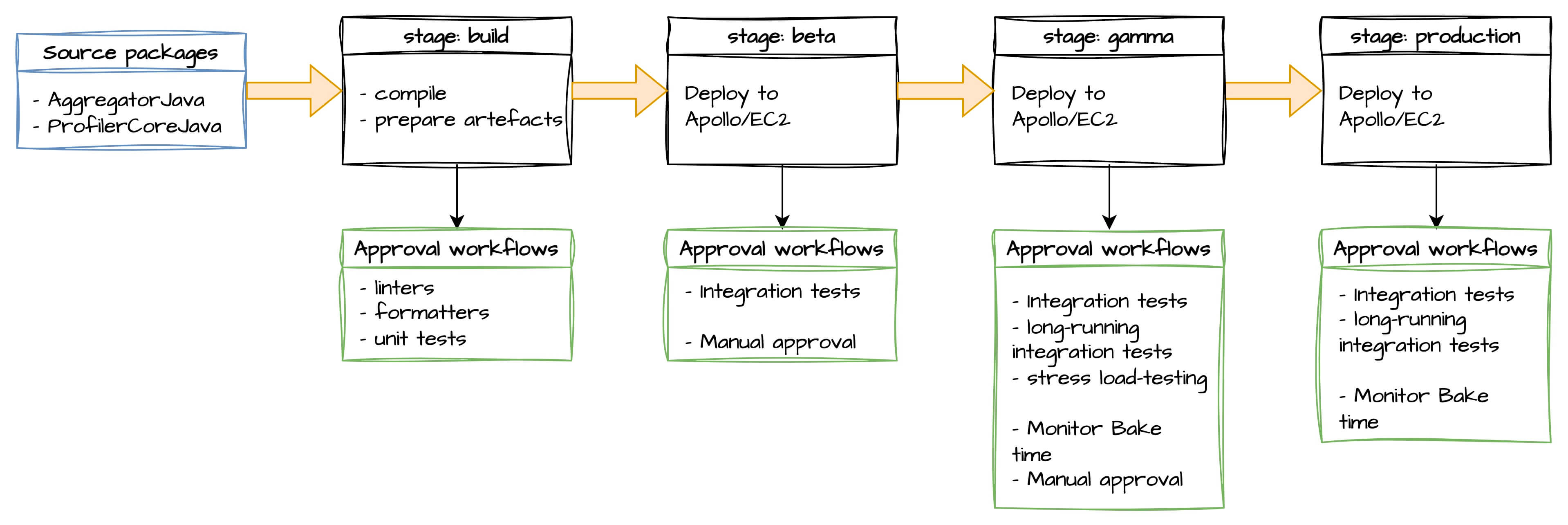

Backend

One of our backend services was the Aggregator, processing all ingested profiling data submitted by all the services using our product, and generating aggregated data that we would then display on the website.

We had one pipeline with 4 stages, including 3 deployment environments (beta, gamma, production). All the environments were in the US.

The source packages column is a collection of Git repositories that will trigger a pipeline execution on every push on the specified branches.

Amazon doesn’t use monorepos, therefore we could have multiple repositories (we call them packages) per service.

The first stage, build, compiles the source code, runs a few static code analysis jobs, and builds the release artefacts.

In our case, the artefacts were the Java .jar files, along with some configuration files.

Proceeding to the beta stage, these artefacts are deployed to the beta environment.

This is a development environment with limited resources (single host), meant to be used only by our team.

The goal of this environment is to guarantee functional correctness of our product, and of our automation.

Stress testing, and high availability is not a goal for beta environments.

Once the deployment completes, we run approval workflows (e.g. integration tests) against the deployed environment, targeting its API directly.

To promote the release artefacts from the beta stage to gamma, we had a manual approval gate.

The manual promotion is not always the default.

We alternated between manual/automatic promotion depending on if we wanted to pause changes from being deployed.

This was useful when we did manual testing in gamma for specific features or to troubleshoot issues.

The gamma stage is usually considered the last pre-production stage at Amazon.

This environment is closer to production, configuration-wise, region-wise, etc.

In some aspects though, gamma and production are not identical. Especially size-wise.

It would be inefficient for all our gamma environments to have the same size as our production environments.

The idea is that gamma is where you do all the tests that need a production-like environment, without affecting actual customers.

A common use-case for gamma stages was to run our load-testing tool, TPSGenerator.

In the case of our Aggregator service, we would mirror the traffic from production in this environment so that we have similar traffic patterns, and similar ingestion data, in order to run experiments on production-identical data and catch issues before impacting our customers.

The approval workflows in gamma are more rigorous than beta, and they included (not exhaustive list):

- load testing

- integration tests

- long-running aggregation tests (e.g. multi hour aggregations)

- security oriented tests

Once all the approval workflows passed, we were manually promoting the release artefacts to the production stage.

A final round of approval workflows were running against the production environment, and if any workflow failed, an automatic rollback would trigger the deployment of the previous artefacts.

One common approval workflow we had across our services was the monitor bake time. For a specified amount of time, the pipeline would continuously evaluate a collection of PMET monitors (internal CloudWatch predecessor) and if any of them transitioned into Alert state within the specified period, the approval workflow would fail, automatically triggering a rollback to the previous release artefacts.

Note: We didn’t do rollbacks in

beta, since it didn’t matter if it was broken for some time. It would only affect our team, and it would give us time to investigate and fix the offending commits. But, we did care forgammaandproduction.

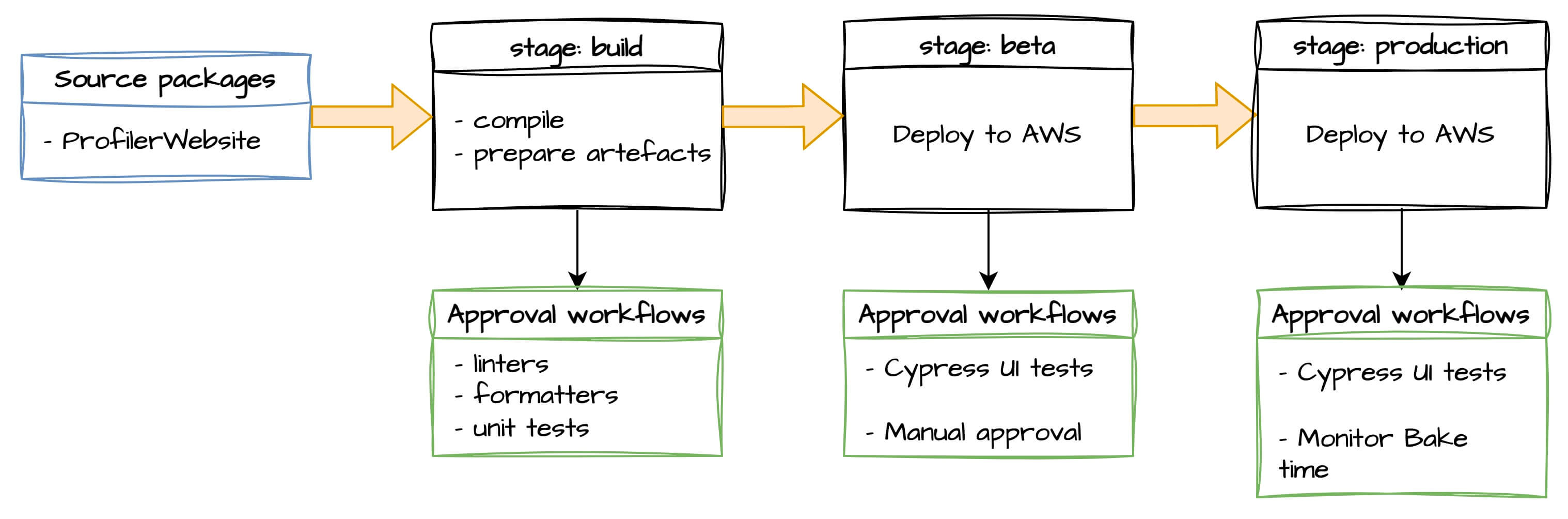

Website

Our website was a Single-Page-Application using React. We had a simpler setup than the backend, using AWS services: CloudFront, S3, and Lambda@Edge.

We had one pipeline with 3 stages, including 2 deployment environments (beta and production).

This is as simple as it can get, but incredibly sufficient for many teams.

This is what I call The Core pipeline, and everyone should try to have this as starting point.

The source packages column is a collection of Git repositories that will trigger a pipeline execution on every push on the specified branches.

The first stage compiles the source code, runs static code analysis jobs, and builds the release artefacts. For the website, the release artefacts were the JavaScript/HTML/CSS files we had to deploy in Amazon S3, along with some AWS CloudFormation templates for the deployment on AWS.

Proceeding to the beta stage, the artefacts are deployed to the beta environment, in AWS region us-east-1.

The approval workflows run once the CloudFormation deployment is done, and verify that the website loads and functions properly using Cypress UI end-to-end tests.

We once again have a manual approval gate before promoting the artefacts to the production stage, same region.

Manual testing against backend API

The beta environment is identical to the production one in this case, since we were using AWS in exactly the same way. The only difference was the domain name.

We could point the website to use any of the backend environments with an in-app toggle.

Within the beta website you could switch between the backend APIs of beta, gamma, production.

We were using the beta environment of the website during development until we felt good to release in production.

Even though we had the manual promotion, we were releasing regularly to production, several times per week to avoid big-bang releases.

Preview environments

Oh the hype… All the modern Platform-as-a-Service products (Vercel, Netlify, Qovery, etc) brag about their automatic Preview Environments per PR.

Even though Amazon tooling didn’t provide this out of the box, it was easy to do it ourselves.

- We made sure that even when running locally on our laptops, we could target any of our backend APIs, in addition to the mocked responses locally.

- We setup one of our development boxes (remote EC2 machine we sometimes used for development), and before publishing a Pull-Request a convenient command would ship the artefacts onto that host and give it a unique URL that we put in the PR description.

We could have used separate AWS accounts/regions and deploy the full website per PR, but at the time we found it easier to just use a host for all the PRs.

AWS - Amazon CodeGuru Profiler

Amazon CodeGuru Profiler is the AWS service my team launched at re:Invent 2019.

At the time, the public product was a small subset of what the internal Amazon Profiler service was capable, and the underlying infrastructure was different. As explained above, Amazon Profiler was using our internal deployment platform (Apollo), and was deployed in only one US region.

CodeGuru Profiler was built from the ground-up on-top of AWS services, using Infrastructure as Code to automate as much as possible, and was deployed across many AWS regions.

There are a lot to cover about launching an AWS service, but in this section we focus only the CI/CD pipelines.

As I mentioned above, we were doing trunk-based development for all our services, and all Pull Requests were merged into a single mainline branch.

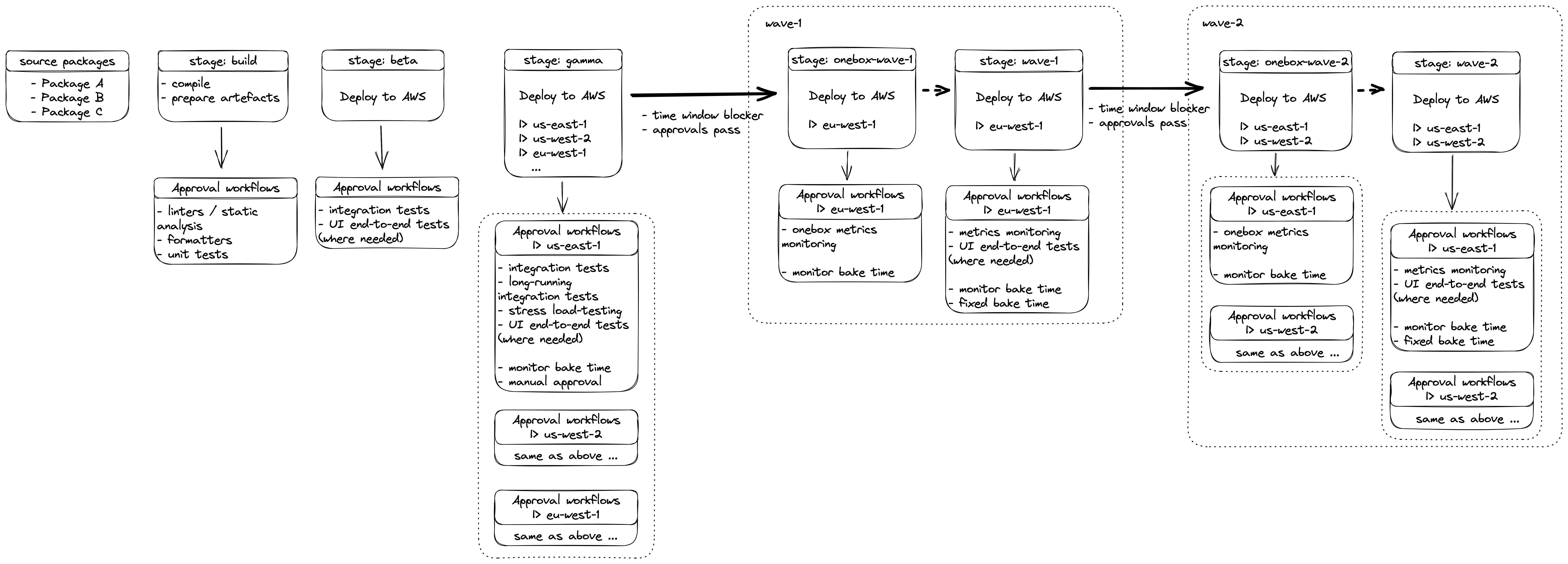

All our backend services, including the website, followed the same CI/CD architecture, therefore I will use a generic service in the example below for simplicity.

(right-click and open in new tab for full preview)

Don’t get frighten by the big diagram 😅 We will go through it piece by piece.

The first half part of the pipeline, up to beta stage, is pretty identical to the showcase of Amazon Profiler, so I will just skip it, and focus on the new parts.

Waves

Every AWS service has to deploy in tens of regions across the world. A region is a physical location of several data centers.

There is a big variance in customer adoption among the regions, which is the dimension of “region size” I will use below.

This is exacerbated by the fact that some services are only available in a specific region.

One example is AWS Lambda@Edge functions.

Even though it deploys your code across many regions to run close to your customers, their own control plane (create and manage your functions) is exclusively in us-east-1. Unfortunately, this means that if you want to use such services you need to deploy part of your infrastructure in those regions.

It is also important to note that deploying one region after the other would take too long for a change to reach all regions.

AWS teams use a wave-based deployment approach where you group multiple regions and deploy to them in parallel, whilst the waves are deployed sequentially. This significantly reduces the blast radius of faulty releases, from automation and configuration issues, to buggy features.

Remember, practicing CI/CD for releasing your software is a way to make sure you ship fast, but also reliably, without breaking many customers.

There are a few different approaches in how you should group your regions, and in what order, but the usual wave-based setup is:

- A small region

- A medium region

- 3+ regions

- 5+ regions

- N+ regions

The exact size of each wave is up to each team, but the idea is that you start slow, and then with each wave you go faster, with more and bigger regions.

The initial slow part gives confidence that your changes are safe, there are no obvious configuration issues, and the business metrics are not dropping alarmingly. Then, you accelerate the deployment in order to rollout the changes to every customer.

Environments

It is common practice in AWS services to have the following deployment environments per region:

gamma: The last pre-production environment for automated, and manual, testing before shipping changes to customers.onebox: Often a single host, but could be a small percentage of the overall production cluster of servers, or even a small percentage of AWS Lambda traffic.production: The full production environment.

To fully benefit from the onebox deployment environment, we need to have proper segmentation of key metrics that we use for alarms and monitors between onebox and rest of production.

Otherwise, it would be impossible to monitor the impact of a change on the onebox environment if the metrics are covering the whole production environment.

Onebox environments are optional, depending on the underlying infrastructure used. For example, when using AWS Lambda in combination with AWS CodeDeploy, you can achieve the same result without having a dedicated environment, since CodeDeploy allows you to do rolling deployments by percentages while monitoring alarms at the same time.

This is what we did in our API services, we used AWS Lambda, and we didn’t have onebox environments.

Pipeline promotions

With the above context in mind, let’s dive into the pipeline itself.

Once the release artefacts are verified in the approval workflows for the beta stage, they are then automatically promoted to gamma.

In gamma we do parallel deployment across all regions.

These environments are not exposed in customers, and the reason we deploy to all regions is to make sure that our configuration, especially infrastructure automation, does not have hardcoded values, or making assumptions about region-specific properties.

After a deployment for a region completes, the corresponding approval workflows start running, even if other regions are still being deployed.

Hopefully, all the approval workflows will pass, and the release artefacts will be ready for promotion in the first production wave, wave-1.

In all the promotions targeting a production environment, there are two usual conditions:

- All approval workflows pass.

- The time window blocker is disabled.

The time window blocker is a feature where we block automatic promotion of changes to the next stage during a specific time window. We use this for important holidays like Christmas and Black Friday, or for restricting deployments only during specific times to avoid breaking production outside the business hours of the on-call, e.g. deploy only during EU/London office hours.

Proceeding to the production wave deployments, we first deploy to the onebox environment, if there is one.

The approval workflow for onebox is often lightweight, mostly monitoring specific metrics, and making sure our alarm monitors do not trigger for a specific amount of time.

Then, the changes are automatically promoted to the full production environment of each region of the wave.

Reminder, that the deployments within a wave are done in parallel.

The approval workflows for each region of the wave start as soon as the corresponding deployment completes. Approvals here include business metrics monitoring, UI end-to-end tests (for certain APIs, and the website), and making sure our alarm monitors do not trigger for a specific amount of time.

In some cases, there is a also a fixed time bake period, where the approval workflow for the wave is essentially paused before proceeding with promoting the release artefacts to the next wave. This is useful when we want to make sure enough time has passed, and enough customers were exposed to the changes released, which could surface issues not covered by the automated or manual tests, and no metric regressed right after the deployment. For example, some issues like memory leaks could become prevalent only after several hours.

The fixed time bake period is not a rule, and I have seen many teams not having them at all, or having them and skipping them unless there is a specific reason.

Once again, when the approval workflow passes and there is no time window blocker enabled, the release artefacts are promoted to the next wave, until all the waves are deployed.

Automatic rollbacks

In case any approval workflow fails in wave N, then the promotion to wave N+1 is blocked, and the offending regional environment rolls back to the previous good version.

This means that some regions within the same wave, could be running different versions of your software than others.

The next version that will flow through the pipeline will at some point arrive at wave N, redeploy to the included regions, and the approval workflows will rerun.

If the approvals pass, then the new version will be promoted as usual to wave N+1. Therefore, all the regions within the wave will now run the same version.

Read more about automatic rollbacks in the article “Ensuring rollback safety during deployments”.

Multiple in-flight versions

My absolute favourite feature of the internal Amazon Pipelines service (also available in AWS CodePipeline) is that each stage of the pipeline runs independently from others. ❤️

This seems subtle initially, but in practice this allows parallel environment deployments of different versions!

For example, you could have v10 being currently deployed in the production environment, v11 in the gamma environment, and v15 in the beta environment, all at the same time in parallel.

This allows for amazing productivity, and velocity, shipping features often and reliably. You don’t worry about coordinating releases, or babysitting a single version throughout the whole pipeline before deploying the next one.

You merge your change, and then it will automatically (with the optional manual promotions occasionally) travel through the pipeline stages as fast as possible, depending on the approval workflows.

If your automated tests are sufficiently good, you can merge multiple times a day, and the pipeline will continuously ship those changes across all your environments automatically.

Conclusion

This was quite a long article, and there are still many things we didn’t cover around CI/CD techniques in the real-world.

I hope this gave a glipmse into how some of the principles and theory of Continuous Delivery (CI) and Continuous Deployment (CD) are applied in practice, and hopefully it gives you confidence to implement some of these techniques in your own team’s release process.